Beale Dixon, who later became general manager of Tillamook County Creamery Association, started his career as a bank teller in the tiny town of Scotts Mills, Oregon. On Christmas Eve 1925, the bank was robbed. The (Salem) Statesman-Journal wrote about the robbery on its 100-year anniversary, and the article is included here as background about a major figure in the Cheese War.

Link to a video timeline:

https://www.statesmanjournal.com/videos/news/2025/12/22/video-timeline-century-old-robbery-state-bank-of-scotts-mills/87832839007/

Dec. 22, 2025

SCOTTS MILLS — If you head northeast past Silverton and turn right about halfway to Molalla, you will find one of the tiniest towns in Marion County.

With a posted population of 355, Scotts Mills is best known as the epicenter of the 1993 “Spring Break Quake” and the filming location for the 2005 Hallmark Hall of Fame movie “The Valley of Light.”

Dig further back and you will discover the town was founded by Quakers and dry until 1965, served as a childhood destination for future President Herbert Hoover, and was the scene of an armed bank robbery on Christmas Eve 100 years ago.

While other Oregon towns also banned alcohol, and Hoover’s local ties are well established, it is surprising to learn not just about the robbery, but that Scotts Mills once had a bank.

Author Marilyn Milne of Eugene stumbled upon the century-old holiday crime while doing research for the 2022 book “Cheese War” about the battle between Tillamook dairy farmers in the 1960s. One of the central figures was Beale Dixon, who worked at the bank in 1925.

“I think it really added color to the book,” Milne told the Statesman Journal. “It was an important element in his early life.”

The former bank building still stands in the heart of Scotts Mills at Grandview Avenue and Third Street. Artifacts from the State Bank of Scotts Mills, from blank checks to teller cages, are displayed nearby at the town museum.

Before exploring robbery and investigation details retrieved from the Statesman Journal archives, let’s set the scene.

Scotts Mills was a bustling town in the early 1900s

Scotts Mills is named after brothers Robert and Thomas Scott. They purchased property in 1866 on Butte Creek, where they operated a sawmill and gristmill.

The gristmill was once considered the most productive west of Minneapolis. Today, the site is a Marion County park.

A post office was established in 1887, and the townsite was recorded by Quaker leaders in 1893.

Scotts Mills supported several businesses in the early 1900s, including two large grocery and dry goods stores, a post office, hotel, blacksmith shop, tin shop, photography gallery, prune drying shed, and coffin factory.

The mills drove the town’s growth, along with the prune-packing industry and mining speculation.

An early coal mining operation spurred hopes that a rail line branch would come through town. Neither panned out.

Bank opens in ‘modern building’ on gravel intersection

Charles Scott, the son of Robert Hall Scott, was the first mayor of Scotts Mills after it incorporated in 1916. He was also one of the founders of the bank.

On Aug. 5, 1920, Scott, A.L. Brougher and J.O. Dixon filed articles of incorporation with the state superintendent of banks and committed $15,000 in capital to establish the new institution.

A charter for the State Bank of Scotts Mills was granted in less than two weeks.

Scott was listed as the president and Brougher, the owner of a general store in town, as the vice president. Dixon, who moved here for the venture from Battle Ground, Washington, was the cashier.

The bank operated in temporary quarters for a few months while a new brick building was constructed, and business exceeded expectations.

Scotts Mills residents and business owners previously had to conduct their banking business in Mt. Angel or Silverton.

The new “modern bank building” was completed by February 1921 on a corner of a gravel intersection. The Capital Journal reported that “the property greatly adds to the appearance of the business section of the town.”

The State Bank of Scotts Mills was considered one of the strongest small-town banks in Marion County, sustained by transactions during the prune and hops growing season. Its deposits averaged about $50,000.

John Orton “Jack” Dixon, the cashier who eventually became president, brought in his younger brother, Hubert Scripps “Beale” Dixon, to be a teller.

The brothers ingratiated themselves with the community, especially during the holidays, organizing a Christmas charity fund and distributing goodie bags to children.

Bank bandits ultimately foiled by time-locked safe

The bank was closed during the noon hour on Christmas Eve. Beale Dixon had just left for his lunch break, and Jack Dixon was filling bags with candy, oranges and nuts in the back room when he heard the door open.

Beale normally locked the door, but Jack soon was confronted by three men armed with revolvers. It isn’t clear whether Beale forgot this time, or how the culprits got in.

The men demanded that Jack open the safe, but he explained he could not because it had a time-locked door that would not open until 1 o’clock. The bandits tried on their own with no success, deciding to wait it out.

The bank had alarms in the vault, on the floor and on the counter, but Jack could not get close enough to activate any of them. The men made him stand with his hands up against the wall, one holding a gun on him.

Beale returned from lunch at about 12:45 p.m. but did not enter the building. He saw one of the men through the window, crouched inside with a gun, and backed away. Other reports say Beale opened the door and was met by one of the bandits before backing away.

He presumed the man did not shoot him because it would have drawn more attention.

While Beale went to call Jack’s wife to see if she had heard from him, and before the sheriff could be notified, the bandits fled town with the bank’s arsenal of guns and a money sack with about $30 in Christmas fund donations.

The guns included revolvers from the inside of each teller cage and a sawed-off shotgun from the vault.

Thirty dollars a century ago would be the equivalent of about $555 today. Had the robbers entered the bank a few minutes earlier, before the safe lock engaged, they could have gotten away with a whole lot more.

Investigation and manhunt for bank robbers begins

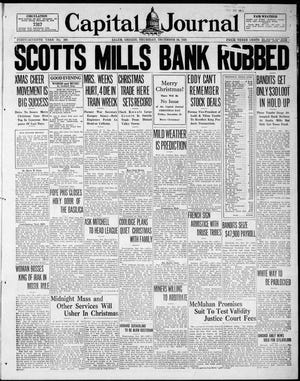

The afternoon edition of the Capital Journal featured a banner headline at the top of the page: “SCOTTS MILLS BANK ROBBED”

The search was underway for three “youthful bandits” who escaped in an automobile after holding Jack as a prisoner for 45 minutes. All were estimated to be under 22 years of age.

A telephone operator saw the men speeding north in a Chevrolet touring car, later found to have been stolen Dec. 10 in Portland, the same night a Troutdale bank was robbed.

The bandits transferred to a stolen Hudson and robbed an automotive garage in the Molalla area before heading south to California. The Chevy was found a few days later in a grove of trees north of Marquam.

The men would eventually be arrested in Redding, California, after getting in a car accident. They were held on federal charges of transporting a stolen car across state lines, but the bank robbery evidence quickly surfaced.

Serial numbers on the guns found inside the vehicle, along with an empty money sack, matched those taken from the Scotts Mills bank. Their photographs were identified by Jack and the bank cashier in Troutdale, where they reportedly stole about $400.

Officials returned George Schroeder to Oregon first. He confessed his involvement in the Scotts Mills robbery, pled guilty, and was sentenced to 10 years in the Oregon State Penitentiary.

Schroeder provided details about the job and three co-conspirators, one of whom did not go into the bank but waited with the getaway car.

None of them appeared to have local ties, and the newspaper coverage never revealed why they targeted Scotts Mills.

Brothers John and Norman Moore were eventually transported back to Oregon by train under custody of the sheriff and district attorney, along with Emil Knorr, who was known by multiple aliases.

They also received 10-year prison sentences.

The Capital Journal reported in February 1926, less than two months after the crime, that all four convicted bank robbers were 17 years old.

Scotts Mills bank falls victim to the Great Depression

Business at the State Bank of Scotts Mills returned to normal for at least a few years, until it fell on hard times with the rest of the nation after the 1929 stock market crash trigged the Great Depression.

Banks failed, businesses went bankrupt, people lost their jobs, and properties were foreclosed.

The bank in Scotts Mills was turned over to state banking authorities by its directors after failing to open on April 28, 1932, according to the Capital Journal.

Jack Dixon appeared in criminal court four days later for allegedly falsifying bank records. Milne’s research revealed that several prominent Scotts Mills citizens raised his bail to keep him out of jail.

He was charged with the coverup of account shortages and bank losses, not personal misuse of funds, and eventually pleaded guilty. He was sentenced to one year in prison, serving only a few months.

Jack and his family left town when support in the community faded. Milne said he went on to work as a lumber mill superintendent before retiring in Eugene. He died in 1977.

Beale eventually became the longtime general manager of the Tillamook County Creamery Association, the cooperative that makes the famous cheese. He was instrumental in the 1960s fight over the future of the co-op, a story told in “Cheese War” by Milne and her late sister, Linda Kirk. Beale died in 1989.

Post office finds home in former bank building

The Scotts Mills Post Office moved into the building on Grandview Avenue a few years after the bank folded and continued to use the teller cages.

The Capital Journal published a story in 1969 about a renovation of the building, reporting that the former bank vault would be turned into a bathroom for the postmaster, eliminating the need for the town’s last functioning outhouse.

Remnants of the bank, including the teller cages, would likely have been salvaged at this time. The federal government signed a long-term lease and supplied new furnishings for the post office.

The post office relocated in 1997 to a new and larger space, and the former bank building has been sporadically vacant since. A construction company rented it for a time from a previous owner.

The building, next door to the Scotts Mills Market, is now locally owned and used for office space.

Bank artifacts displayed at historical society museum

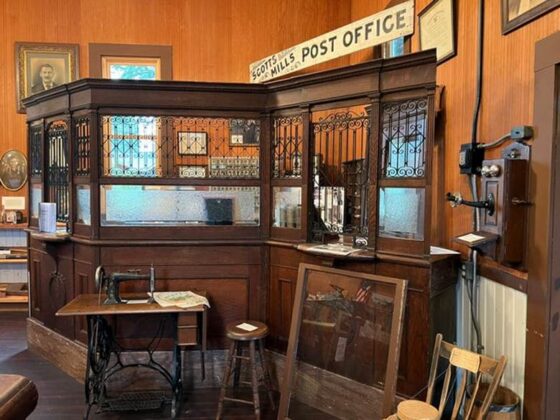

The State Bank of Scotts Mills and its Christmas Eve day robbery may only be footnotes in town history, but the teller window counter remains a conversation piece at the local museum.

The dark oak piece with marble trim, filigreed brass grills, and etched windows is prominently on display just as you enter the historic church building that now houses the Scotts Mills Historical Society Museum.

Milne, whose research has continued since the book, visited the museum in September.

“To have that countertop and fancy-looking filigreed teller cage set up and to be able to see it in the museum is amazing,” she said, even more excited about finding a hole drilled in the countertop. “I geeked out. There it was.”

She explained that the hole housed one of the bank’s alarms, using a bicycle spoke as the mechanism below and concealed above by a stack of gold coins. The removal of the coins would trigger the alarm.

No one knows whether the bank bandits that day 100 years ago would have seen the gold coins or overlooked them because they were so focused on the vault and safe.

The teller window counter is on display in part thanks to the late Margaret Splonski Gersch, whose likeness graces a mural in front of the museum.

Her daughter, Patti Pike, said she saw the piece several years ago in an exhibit at what is now Willamette Heritage Center in Salem.

“That doesn’t work for me,” Gersch told her daughter. “It should be in Scotts Mills.”

The teller window counter and other materials were donated to Mission Mill Museum in 1971 and transferred to the Marion County Historical Society in 1990. The two Salem organizations merged in 2010 to become Willamette Heritage Center.

It took a few years, but the teller window is now on loan from Willamette Heritage Center.

The Scotts Mills Historical Society Museum is open on the second Sunday of each month from March through October, or by appointment.

Capi Lynn is a senior reporter for the Statesman Journal. Send comments, questions and tips to her at clynn@statesmanjournal.com.